"Operation Ajax"

INTRODUCTION

The study of history is open to interpretation, and

interpretations often differ greatly as to what happened and why in any

significant historical event. This assignment examines three secondary accounts

or scholarly interpretations of the CIA-engineered coup in Iran in August 1953

and one declassified primary source, the famed "Wilbur report," a

secret agency account of the events written in 1954 (shortly after the coup) by

one of the CIA's main operatives on the ground in Tehran during the events. The

CIA declassified the "Wilbur report" in 2000, albeit with some of the

information redacted, and it immediately became an invaluable source of

information regarding the coup. A primary goal of this assignment therefore is

to prompt students to think about the differences between primary and secondary

sources in the study of history.

|

|

|

|

|

|

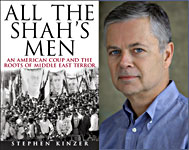

Stephen

Kinzer's book All the Shah's Men (2003) documents the 1953 coup in Iran |

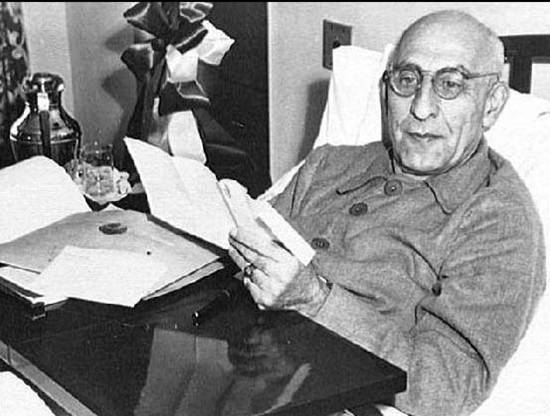

Former Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq

(1882-1967) |

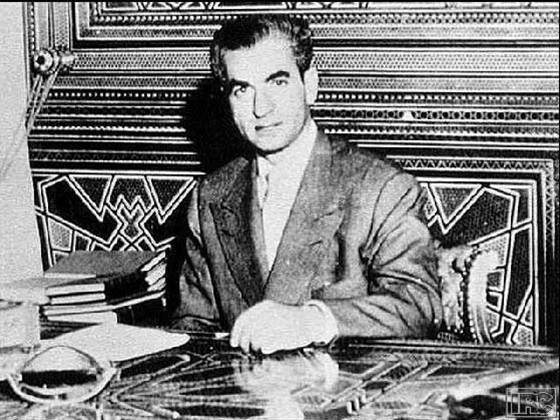

Mohammed

Reza Shah Pahlavi, the "Shah of Iran" (1919-1980) |

CIA agent

Kermit Roosevelt (1916-2000), grandson of Theodore Roosevelt |

Before beginning the assignment view this August 2013 CNN report

on the CIA's release of documents pertaining to its secretive

1953 actions in Iran, kept classified for sixty years, admitting its involvement

in the coup (and remember, sources of this nature are also secondary accounts,

that is, inherently biased sources that interpret

the events described after the fact):

CIA's

1953 "Operation Ajax" (4:29).

|

There

are three steps to this Assignment: Step

1:

Read these three accounts of "Operation Ajax" and look for key

differences between them in content and tone (Note: the directly quoted

descriptions from the texts are in regular font, additional material is

italicized). Each of these secondary sources are from the early 1990s, before the publication of the Wilber

report and other material pertaining to the coup, so the authors did not have access to a great deal of

primary source material in writing these accounts. Thus

their interpretations are based largely on the recollections of the lead CIA

agent in the coup, Kermit [or Kim] Roosevelt, various British intelligence

officers and diplomatic personnel, the Shah, and several eyewitnesses. For a

more recent, comprehensive account of the coup and its aftermath based on

declassified CIA material see Stephen Kinzer's All the Shah's Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East

Terror (2003). |

1.

|

|

Daniel Yergin from The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money

and Power (1993), pp. 469-470. Yergin, a Pulitzer-prize

winning American author, speaker, and economic researcher, is also co-founder

and Chairman of the Cambridge Energy Research Associates, a consultant group

for major oil companies. In 1993 The Prize aired as a PBS series

which, according to the

media criticism group FAIR, was funded "by Paine Weber, a company

with major oil interests. . . . Almost every expert featured [on the series]

was a defender of the oil industry." |

Yergin asserts that the plan was to have General Fazlollah Zahedi, who was loyal to the Shah, challenge Mossadeq and demand his ouster as Iran's Prime Minister. Yergin's account:

Operation Ajax unfolded over

the middle of August 1953 with great suspense and high drama. There were code

names for all the main actors. The Shah was "Boy Scout"; Mossadeq, "the old bugger." One of [Kermit]

Roosevelt's code names, owing to a border guard who misread his passport, was

"Mr. Scar on Right Forehead." Waiting nervously over several days in

the home of one of his operatives in Tehran, Roosevelt took to playing and

replaying the song "Luck Be a Lady Tonight," from the musical Guys

and Dolls, which was then a great hit on Broadway. It became the theme

song for the operation.

But it looked like bad

luck at the beginning. The operation was scheduled to start when the Shah

issued an order dismissing Mossadeq, but delivery of

the order was delayed three days, by which time Mossadeq

had been tipped off, either by one of his supporters or by Soviet

intelligence. He had the officer who carried the order arrested and

launched his own effort to topple the Shah. General Zahedi went into hiding. Mossadeq's supporters and the Tudeh

[Communist] party held the streets. They smashed and tore down the statues

of the Shah's father in the public squares of Tehran. The Shah himself

took to flight, first to Baghdad, [then to Rome] ...

But the next morning

[August 19] the tide turned in Tehran. General Zahedi held a press

conference at which he handed out photostats of the Shah's order dismissing Mossadeq. A small pro-Shah demonstration grew into a

vast, shouting crowd, led by tumblers doing handsprings and wrestlers showing

off their biceps and giant weightlifters twirling iron bars. Growing even

larger, it swarmed out of the bazaars [markets on the outskirts] to the center

of the city to proclaim its hatred of Mossadeq and

its support for the Shah. Pictures of the Shah suddenly appeared to be

plastered everywhere. Cars turned on their headlights to show support for

the Shah. Though street fights broke out, the momentum was clearly with

the pro-Shah forces. The Shah's dismissal of Mossadeq

and appointment of Zahedi as successor had become known. Key elements of

the military rallied to the Shah, and soldiers and police dispatched to quell

pro-Shah demonstrators instead joined them. Mossadeq

fled over the back wall of his garden, and Tehran now belonged to the Shah's

supporters.

The Shah allegedly said

upon hearing the news in Rome, "I knew that they loved me," referring

to the Iranian people.

2.

|

|

T. E. Vadney from The World Since 1945 (2nd

edition, 1992), pp. 213-214. Vadney

is from Canada and was a Professor of History at the University of Manitoba.

He tends to be very critical of US foreign policy in his textbook. |

Before the coup the US

had supported a [British]-sponsored boycott of Iranian oil on world markets,

and the loss of revenue hurt Mossadeq's government

badly. By late 1952 and early 1953, therefore, the time to strike was

opportune, because Iran was in financial distress. ... Kermit Roosevelt of the

CIA... went to Iran and set the conspiracy in motion. The plan was for the

Shah to dismiss Mossadeq as prime minister, and

install General Zahedi, who had collaborated with the Nazis during the Second

World War. But Mossdadeq found out about the

plot, with the result that the Shah fled first to Baghdad and then to

Rome. Large anti-Shah demonstrations then followed, with the Tudeh [Communist Party] in the vanguard, but the CIA was

also secretly financing demonstrations against Mossadeq's

government. The Prime Minister feared that further violence by his

partisans would cost the government support, and that he was losing control of

events. He therefore called out the army, but it was a right-wing

stronghold. Moreover, calling out the army caused dissension between the Prime

Minister and the Tudeh, and hurt their efforts to

resist the CIA-Shah coup. Instead of protecting Mossadeq's

supporters, the army moved against the crowds of Tudeh

members and other anti-Shah forces. Mossadeq was

overthrown and jailed. The coup had not gone exactly according to plan,

but the result was the same.

Vadney raises several other points as well:

- The net profits of the

Anglo-Iranian Oil Company between 1945 and 1950 were almost three times

the royalties the company paid to Iran, which was one of the main reasons

for strong sentiments against the company.

- When the Parliament

voted to nationalize oil in 1951, he writes, "Popular demonstrations

indicated widespread support for such action," and Mossadeq himself "enjoyed a great deal of

support."

- During Mossadeq's rule, the Communist Tudeh

Party (formerly banned) operated openly, which made the United States

suspicious of the Iranian Prime Minister.

- The Shah attempted to

dismiss Mossadeq in 1952, but popular

demonstrations brought about his return as the Shah backed down.

- After Mossadeq's ouster and the Shah's restoration Iranian

oil remained nationalized; the Shah granted US oil companies an equal

share of the country's oil production to that of the Anglo-Iranian Oil

Company, which previously had controlled almost all of it.

- Western oil companies secretly

agreed to limit Iranian oil production "in order to control the

Shah's revenues and keep him subservient to Western interests."

- Finally, he adds that

"the Shah instituted what became one of the world's most repressive

dictatorships, aided and abetted by the CIA," which created the

Shah's infamous secret police, the SAVAK.

3.

|

|

William Shawcross

from The Shah's Last Ride (1990), pp. 67-71. Shawcross (b. 1948) is a British

free-lance journalist, author, and television commentator known especially

for his work on Southeast Asia. He writes and lectures on international

policy and has written for several publications, including Time, The Washington Post, and Rolling

Stone. He has also authored numerous books on topics ranging from

Cambodia, Iran, and the Nuremburg trials, to a biography of Queen Elizabeth

published in 2009. |

Shawcross repeats the

basic plan for the Shah to dismiss Mossadeq and

replace him with General Zahedi.

Meanwhile,

Roosevelt would give two agents several hundred thousand dollars out of a

substantial slush fund the CIA had established in Tehran. This money was

to be handed out to thugs from athletic clubs and the poor of the South Tehran

slums to encourage them to demonstrate in favor of the Shah....

At first the plan did not go well. Mossadeq

simply arrested the Shah's messenger..., declared that he had forestalled a

coup and issued orders for Zahedi's arrest. But the general was already in

hiding on a friend's estate. He appealed to the Army, still largely loyal

to the Shah. At first, the streets of Tehran were held by Mossadeq supporters and members of the Tudeh

Party. Mobs with red flags tore down the graven images of the Shah's

father, Reza Shah, and cried "Yankees go home."

Thinking the attempt had failed, the Shah himself panicked and fled with [his

wife] Soraya in a small plane to Iraq.... At first the mobs in Tehran had

all been anti-Shah. Gradually, however, the tide began to

turn. Soldiers appeared in the streets and showed that the Army was still

loyal to the Shah and to Zahedi. Then the CIA's paid demonstrators,

organized by Roosevelt's two intelligence brothers, marched up from South

Tehran and shouts "Long live America" began to prevail over

"Yankees go home." The Shah's picture was plastered on walls and

windows. Pro-Shah and anti-Shah groups fought in the streets. Mossadeq was toppled; Zahedi was embraced by the crowds and

assumed the premiership....

Then, drinking champagne with journalists, [the Shah] flew home to a Tehran in

which his supporters had tried to re-erect the toppled statues of his

father. He told Kim Roosevelt of the CIA, "I owe my throne to God, my

people&emdash;and to you."

Many of his opponents considered that the role of the CIA was more crucial than

that of the Almighty. It is certainly true that the actions of the CIA and

MI6 [British intelligence] were important. But alone they could not have

removed Mossadeq. The demonstrations were indeed

provoked and begun with MI6 and CIA money&emdash;no one knows how much was

spent&emdash;but money alone could not adequately explain the way in which

the protests rushed so fast through the city. The costs of Mossadeq's

policies had come to seem too high to too many people and there was already

widespread dissatisfaction with his rule. The CIA and MI6 provided a

spark, but the dry tinder was Iranian. Nonetheless, to many Iranians the

events proved the Shah was an American if not a British puppet.

Shawcross further adds that after the coup replacing Mossadeq with Zahedi, the US approved hefty loans to Iran

that had been on hold since the oil embargo began in 1952. He notes that,

while there was no bloodbath, many of Mossadeq's

supporters were jailed and his foreign minister was executed. Mossadeq lived under house arrest until his death in 1967.

Step 1 (cont'd):

What differences did you notice in these secondary sources? How might one

account for these differences? Respond in 2-4 sentences.