Plants are everywhere to the point that we easily stop noticing them. It’s something that Leah Sobsey is trying to change, with help from two renowned American authors who were also plant enthusiasts.

The associate professor of photography at UNC Greensboro’s College of Visual and Performing Arts got to work with the plant and flower collections of Emily Dickinson and Henry David Thoreau. Using photography techniques contemporary to the authors, she placed these plants’ histories in the context of the present day, demonstrating how they adapt – and are lost – through climate change.

“For me, it’s somewhat of a reaction to the digital world, to be more aware and literally in touch with these plants,” Sobsey says. “One foot in history and another foot in the present, and even looking forward.”

This Earthen Door

Much of Emily Dickinson’s groundbreaking poetry was only uncovered after her death. In life, she challenged the social expectations for a young, unmarried woman of 19th century Massachusetts and preferred the solace of the garden to receiving guests at the family home.

“She was known as a gardener, not a poet,” Sobsey explains. “A good term for her is ‘eco-reporter.’ She was so connected to the natural world that it became a part of her writing.”

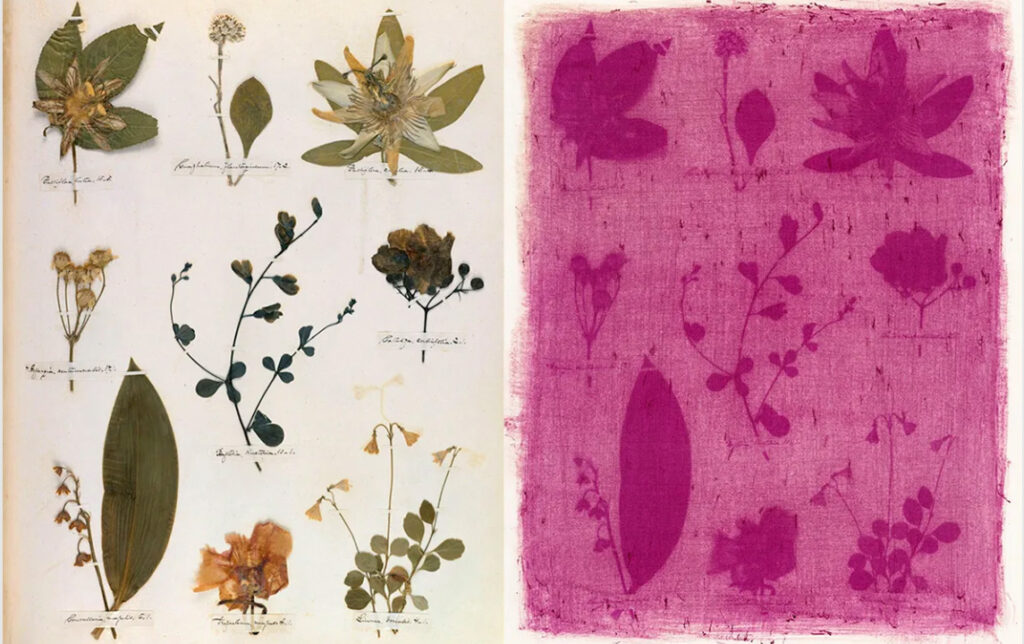

Dickinson kept an herbarium – a book of pressed plants – that is now housed at Harvard University, but it has become so fragile that no one can touch its 424 specimens. Sobsey had to grow her own samples with collaborator Amanda Marchand – half the plants in Sobsey’s garden in North Carolina and the other half in Marchand’s homes in Canada and New York.

Using a 19th century photographic process known as anthotype, they ground petals to make an emulsion, a fine layer of pigment that bleaches out during exposure to UV light, to create the final images of their plants. They called their exhibition “This Earthen Door,” a line from one of Dickinson’s poems.

They partnered with two botanists to review the plants’ histories. “We learned what would have been used as medicinal plants during Dickinson’s time, which were toxic, which were invasive,” says Sobsey. “Together, we have all these plant stories and visuals, all through the lens of Dickinson.”

In Search of Thoreau’s Flowers

Sobsey also collaborated with scientists, artists, and writers for an exhibit called “In Search of Thoreau’s Flowers: An Exploration of Change and Loss” at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. For this project she used the cyanotype process, which employs iron compounds and UV light to create a striking Prussian blue image. Sobsey printed the final images on large plates of glass and backed them with 23-karat gold.

“The gold creates this kind of reverence for the plants,” she explains. “It also acts like a mirror, so you can see yourself reflected in the plant.”

Henry David Thoreau was one of the most influential authors of transcendentalism – a literary movement centered around romanticism, emotion, individualism, and nature. Harvard maintains 648 plant and flower specimens he collected around his home. A third of them are endangered or extinct.

Sobsey used shades of blue to illustrate the fates of those flowers. “The ones that are light blue are thriving or adapting to climate change. The ones that are dark blue are in severe decline. You can really see the visual of the loss on the wall.”

Clear Picture of the Past

The photography techniques have another layer of meaning. Though both are attributed to Sir John Herschel, Sobsey wants to celebrate the women who helped develop and popularize them. In the case of cyanotype, it was Anna Atkins, the first to publish a book of cyanotype illustrations in 1843.

“She sort of had one foot in science and one foot in the photo world,” says Sobsey. “Her book was instrumental in changing the way that we understood plants and science.”

The anthotype photography honors mathematician Mary Somerville, who experimented with the technique at her home in Scotland concurrently with Herschel. “She doesn’t really get the credit,” says Sobsey. “Women weren’t included in the sciences in that way. So, this was a nod to women who have been left out of the conversation in the worlds of science and art.”

A Nod to the Future

Nature has always been part of Sobsey’s work. Her past residencies include studying landforms at the Grand Canyon Museum. At UNCG, she and Tara Webb, lecturer of costume technology in the School of Theatre, started a pollinator garden for students.

Working with the herbariums gave Sobsey a deeper appreciation for plants in general. “We have this way of not noticing plants in the same way that we would animals, like the loss of an animal we feel more than the loss of a plant. And yet, we wouldn’t be here without plants.”

“This Earthen Door” debuted at the 2023 PHOTOFAIRS New York and is now on display at the Missouri Botanical Garden. “In Search of Thoreau’s Flowers” remains at the Harvard Museum of Natural History.

Sobsey wants to use her artistic talent as a springboard for discussion. “During all of this, I thought about the struggle of climate change, living in this moment where it feels out of our control. I thought about what individuals can do to make a change.”

She also wants her work to instill a sense of hope. She says, “Without hope, we can’t really imagine a world that we would want to live in.”

Story by Janet Imrick, University Communications

Photography by Sean Norona, University Communications

Additional photography courtesy of Leah Sobsey and Amanda Marchand