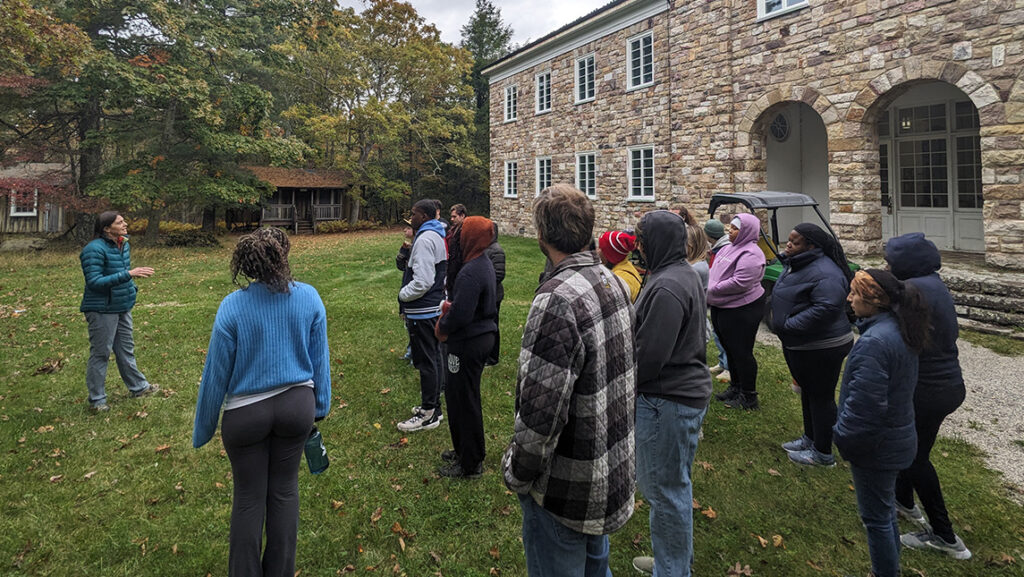

During the fall break in 2023, a group of undergraduate and graduate students ventured from UNC Greensboro’s campus to a remote mountain ridge in Virginia. They toured a tower full of sensors recording weather, air flux, pollution levels, and other environmental factors around the Mountain Lake Biological Station.

They went out to the stomping ground of Dr. Bryan McLean, assistant professor of biology, where he showed them how to trap and release small mammals like shrews, mice, and voles.

The experience was part of UNCG’s new “Introduction to Biodiversity Data” course, which lets students in on the ground floor of the scientific community’s new and expanding open-access databases.

For McLean, building databases is just one step in his work on the National Science Foundation (NSF)’s Ranges project. Emerging scientists like those at UNCG must know how to use that data without feeling overwhelmed by the glut of information now at their fingertips.

“We’re kind of awash in data as a society,” says McLean. “You have to teach people how to go to the websites, how to use the landing page, how to search, and how to understand the results you get back.”

Wild World of Data

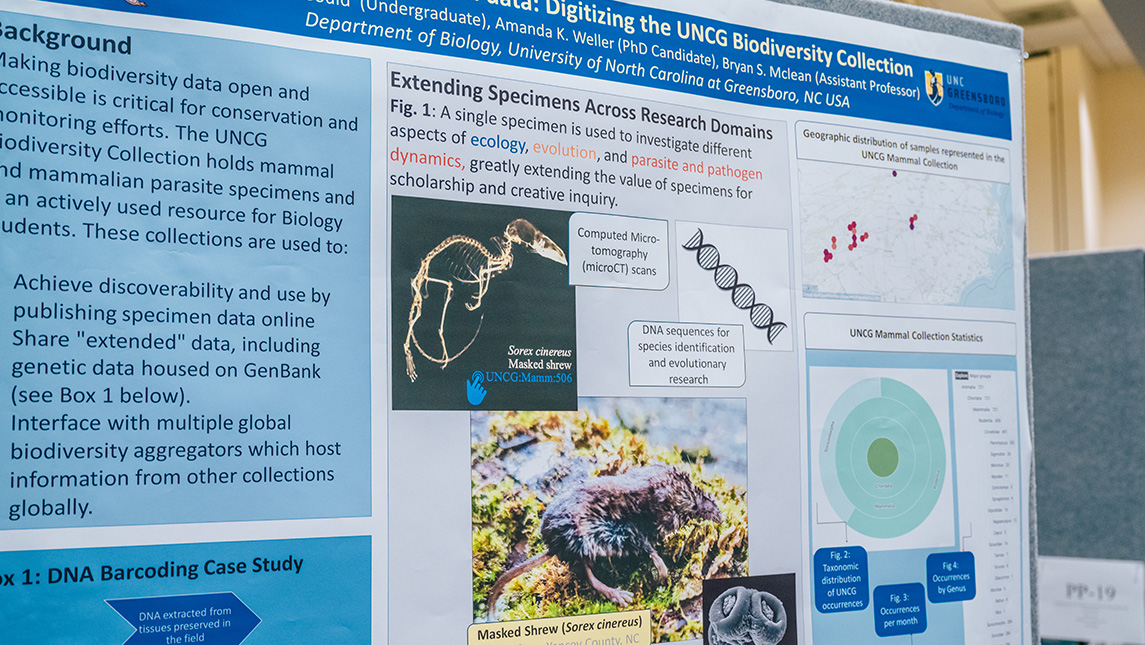

Biodiversity is the study of the variety of wildlife in an area, emphasizing individual sightings and observations. All that research used to be spread out across smaller databases, museum filing cabinets, scientist’s offices, and even civilian hikers’ personal phones. As principal investigator for Ranges, McLean oversees more than 20 institutions across the United States putting their specimen data and research notes online for anyone to access from anywhere.

“When you go online, you can find a lot of collection data,” he says. “Scans of physical specimens, an image of an herbarium sheet, 3-D imagery of an insect specimen or vertebrate skeleton. Lots of different things.”

A separate NSF “Building Research Capacity of New Faculty in Biology” award went toward designing the biodiversity course for UNCG. Students attended virtual lectures with students from Georgia Southern and Northern Michigan Universities. They heard from experts, including informaticians and a field ecologist from the NSF’s National Ecological Observatory Network.

They combined the lectures with hands-on research in UNCG’s labs and during their trip to Mountain Lake Biological Station at the University of Virginia. There, they spent their fall break studying at the 259-hectare reserve adjacent to the Jefferson National Forest. Its natural lake, virgin forests, and bogs make it a popular spot for scientists to study mammals and aquatic life.

“All of our great work sometimes happens in a small vacuum,” says McLean. “So, we can train more people and show them all this biodiversity information moving online at a rapid pace.”

Another guest speaker for the course was Tony Iwane, outreach and community coordinator of iNaturalist. This app allows people to upload photos and identify plants and wildlife wherever they go. This casual biodiversity research by nature lovers, sometimes known as “citizen scientists,” is a boon to the broader ecology community.

“The volume of citizen science data out there is huge,” says McLean. “It’s a major component of biodiversity data. The class teaches students about these different sources of biodiversity data.”

Assembling the Big Picture

When scientists look at the data gathered from individual nature observations, they can put together a picture of ecological trends, historic timelines, species relationships, and evolutionary or physiological responses to food scarcity and disease.

“There are multiple axes of biodiversity knowledge,” McLean explains. “We start with occurrence records – essentially what kind of species, where it appeared, and when. Then you can build out your knowledge from that – what were they doing, what was their morphology, were they breeding or not? Ranges specifically builds up to that next level of data while always linking it back to the individual animal.”

Biodiversity research is key for local and international conservation efforts. It can relay what kind of toxins are building up in an area. It can help track new pathogens carried by local parasites. The United Nations and other global bodies care about the environmental and health-related data that could eventually influence major intergovernmental policies about climate.

But biodiversity access is not limited to such large-scale initiatives. UNCG students can narrow their scope to focus on a specific trait for their research. McLean’s students in one graduate seminar contributed to a recently published paper, using biodiversity data to track litter sizes of small mammals.

“We were able to track life history evolution through 40 species across North America,” says McLean, “And with a lot more data from single individuals than we ever would have been able to collect on our own.”

Story by Janet Imrick, University Communications

Photography courtesy of Dr. Bryan McLean, College of Arts and Sciences

Additional photography by Sean Norona, University Communications