When Dr. Jewel Parker, a 2024 graduate of UNC Greensboro’s History Department, learned that her dissertation had won the C. Vann Woodward Dissertation Prize, she was stunned.

“It’s one of the most competitive awards in Southern history,” she says. “I truly didn’t expect it.”

The award, bestowed each November by the Southern Historical Association, recognizes the best dissertation on Southern history defended in the previous calendar year.

The project was directed by Dr. Greg O’Brien, professor and department head of history. “It’s a coup for our department,” O’Brien says. “This prize is typically dominated by flagship institutions and Ivy Leagues.” The distinction places Parker and the university’s graduate history program among the strongest in the nation.

The C. Vann Woodward Prize recognizes scholarship that advances the field. Parker’s project does so by bringing together three medical traditions that historians often study separately: Native American botanical and spiritual healing practices, African and African-descended healing knowledge developed during and after enslavement, and European medical traditions transplanted to the Americas.

“No one had ever tried to integrate all three,” O’Brien explains. “We’ve had studies of enslaved healers, studies of European medicine, and studies of Native medicine—but not a comprehensive picture. Jewel created one.”

America’s medical history

Parker traced the history of Native Southerners as the region’s first medical experts. Their knowledge—built through thousands of years of experimentation with local plants and ecosystems—became the foundation on which European settlers and enslaved Africans learned to heal in the Americas.

Imagine encountering—with no prior knowledge of its existence—a rattlesnake.

Cherokee and Choctaw healers, says Parker, warned Europeans when they arrived about the dangers the snakes posed. They also identified roots that could help with bite severity if applied quickly.

“Our modern pharmacopeia still relies on compounds derived from botanical remedies used by these communities,” Parker says. “That history has largely been forgotten. My goal was to recover the origins of the medicines we use today and give credit where it’s due.”

Parker and O’Brien

Examples in Parker’s dissertation include American ginseng, valued for pain relief and overharvested after settlers learned of its medicinal uses, and willow bark, used by Native healers for its pain-reducing properties long before its active compound inspired modern aspirin.

The botanical practices were sometimes learned through trade and intermarriage, sometimes observed and recorded, and sometimes extracted under coercive or exploitative conditions.

Parker’s work highlights this complex, everyday intercultural exchange that shaped the region’s medical landscape.

Ultimately, she hopes her efforts encourage scholars and the public alike to rethink the origins of American health care.

“Our modern medicines are deeply rooted in Native and African knowledge,” she says. “We should remember that, honor it, and continue learning from it.”

A national honor rooted in UNCG Training

For Parker, who now teaches at Appalachian State University, her path to the award began long before her dissertation defense. She credits O’Brien’s mentorship as essential to her success.

During her time at UNCG, he encouraged her to apply for competitive funding—and to make a case for why her work mattered. The results funded her to travel to archives across the country, where she uncovered the documents that brought her project to life.

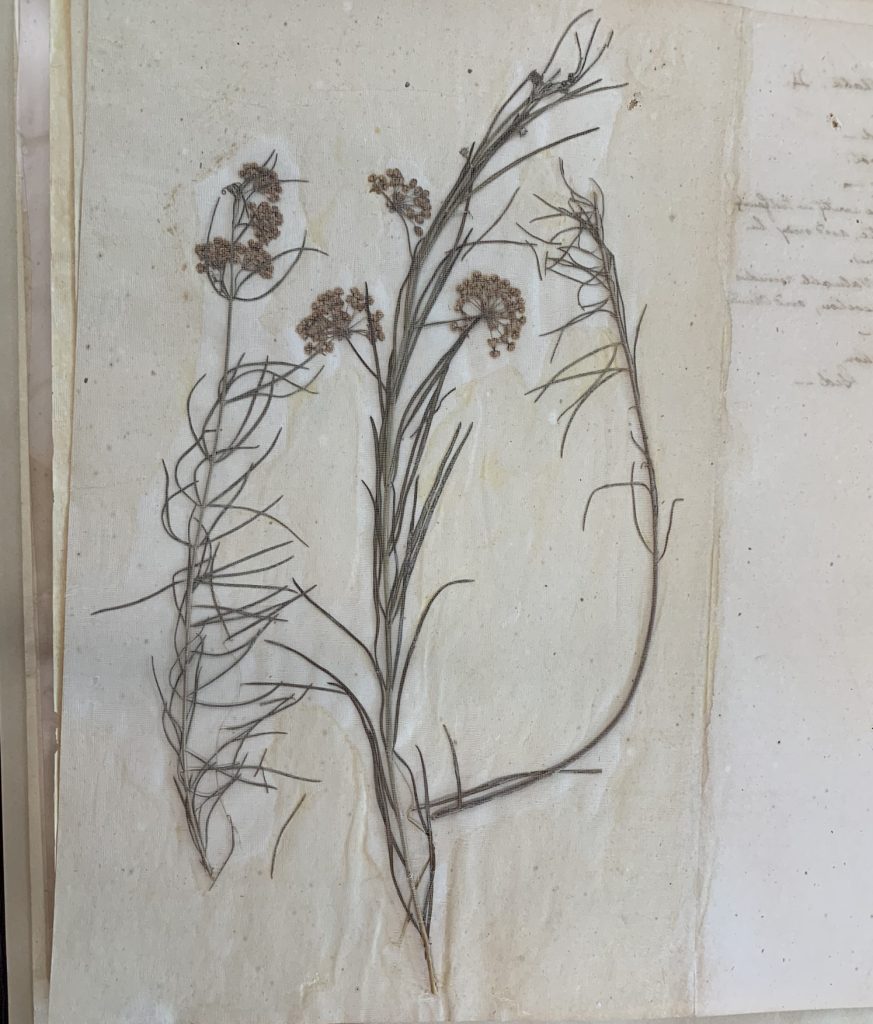

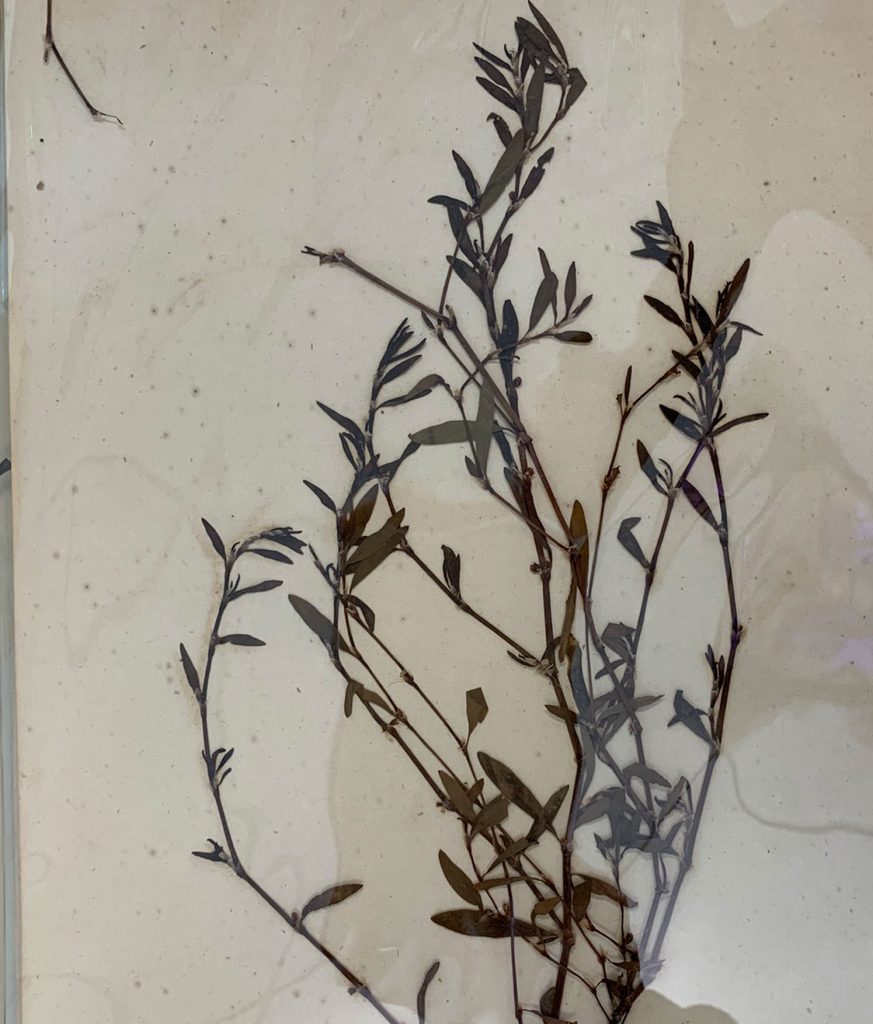

Samples of pink snakeroot, rattlesnake master, and knottgrass (l-r) from the Gideon Lincecum Collection at the UT Austin Briscoe Center. “Lincecum was a physician who spent some time living among the Choctaws in Mississippi and learning directly from a Choctaw doctor,” says Parker. “He writes that the Choctaws viewed pink snakeroot as one of their most valuable remedies against snakebite, while rattlesnake master was a Muscogee remedy. Knottgrass was a Choctaw remedy for preventing miscarriages.”

“UNCG faculty were incredibly supportive,” Parker says. “Dr. O’Brien pushed me academically, helped me secure research funding, and taught me how to communicate my work clearly. That mentorship shaped the historian I became.”

Her gratitude is shared: O’Brien won the UNCG Excellence in Graduate Mentoring Award in spring 2025, with Parker as one of the students who nominated him.

“She did innovative, important work,” O’Brien says. “It’s exciting to see the wider field recognize that. This award is a major accomplishment for her—and a real point of pride for our department.”

By Sierra Collins, Division of Research and Engagement